Three passionate advocates teamed up with a gifted artist to create an inclusive, accessible flyer about important educational rights and services for students experiencing homelessness.

Five key takeaways:

Five key takeaways:

- Current posters and brochures about the rights, protections, and services that the federal McKinney-Vento Act provides to students experiencing homelessness can be wordy and complicated, making critical information inaccessible to those who need it most.

- Current posters and brochures are also not representative of Washington’s diverse communities.

- Clearer, more accessible information bolsters school and community outreach efforts to better support more students and families experiencing homelessness, including those who are living doubled-up.

- A creative and unique collaboration between Building Changes, Longview Public Schools, and the Washington State Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds was borne from the desire to address these challenges.

- A newly designed McKinney-Vento Rights and Services School Flyer is now available for use by schools and school districts.

Students experiencing homelessness have the right to an education despite their housing status, but many are not aware of their rights nor the assistance available for them to stay in school. Under the federal McKinney-Vento Act, school districts are required to provide support and services for students experiencing homelessness. Posters and brochures created by government agencies about the McKinney-Vento Act have been distributed in schools, but they are wordy and confusing—too complicated for many school staff to explain and too difficult to understand for students and families who need the information the most.

But what if information about educational rights and services under the McKinney-Vento Act was further simplified so that most people, despite language barriers and literacy levels, could understand it? What if images from existing posters could be updated to be inclusive and reflective of people’s diverse backgrounds and housing situations?

These are the types of questions Mehret Tekle-Awarun, Amy Neiman, and Rose Spidell asked as they worked together to design a McKinney-Vento flyer that would better serve students and families experiencing homelessness. Mehret is a senior manager at Building Changes who focuses on education; Amy is the director of state and federal programs at Longview Public Schools; and Rose is a senior education ombudswoman at the Washington State Governor’s Office of the Education Ombuds (OEO). Using grant money from Education Leads Home, Mehret, Amy, and Rose embarked on a project to create a flyer that would be more accessible and inclusive than what has been distributed in schools so far. Such a flyer could go a long way toward improving school district outreach to students and families experiencing homelessness and getting them the supports they are eligible for and need.

Creating a new flyer may seem like a small project in the grand scheme of supporting students experiencing homelessness. However, it is important to understand why updating a flyer to get information to the people who need it is one of many crucial steps that needs to be taken to help move students and families experiencing homelessness toward educational justice.

“Where do I fit in? I still don’t even know who to call.”

Existing government- approved posters and brochures about educational rights and services available under the McKinney-Vento Act are densely worded and have the kind of formal tone common in government documents. As a result, they are difficult to understand for everyone, especially those with low language literacy levels and those whose primary language hasn’t been represented in translated documents. The 2019 U.S. Census reported that almost 20% of the population in Washington spoke a language other than English at home. Additionally, the U.S. Department of Education says that 54% of the U.S. population between 16 and 74 years old reads below the sixth grade level. To create outreach publications that will serve everyone, it is important to take into account people’s diverse education levels and cultural backgrounds.

“If you’re a provider or someone like us [at Building Changes] who wants all information, we want to know the full detail. But for families who have K–12 students, nobody has time for that when you’re in a crisis,” said Mehret. She went on to explain that not only are existing posters and brochures hard to decipher, too much information can overwhelm parents and students. “Students will still ask, ‘Where do I fit in? I still don’t even know who to call even if I see this flyer.’ Often, the flyers don’t have a person’s number, but it is the school district’s phone number, and you’re left going down a rabbit hole. A lot of these compliant, government-approved, state agency flyers aren’t really what families need immediately,” she said.

While Mehret provides a bird’s eye perspective on student homelessness in Washington, similar concerns about the lack of clear information have been apparent at the state and local levels. As an ombudswoman at OEO, Rose has had the opportunity to work with students and families who may have been eligible for services under the McKinney-Vento Act. From her experience, some of the students and families she has helped did not know about available supports until it was too late. She explained how lack of clear information further excludes students experiencing homelessness. “It may not come clear until somewhere down the line, or there may have been confusion, or it may not come up until after a student has already made a move from one school to another, or struggled with enrollment. If you know about services provided by the McKinney-Vento Act early, then you avoid leaving the school and trying to get into the next one. Delay in education is just so common for students experiencing homelessness,” she said.

Confusion about whether a student is eligible for services is common, especially for those living in doubled-up households whose residential status does not neatly line up with any of the federal definitions of homelessness. When someone is doubled up, they do not have a permanent place to call home and are temporarily sharing housing with other people due to loss of their own place, economic hardship, or any other reason that prompts a move to a short-term, shared living space. The Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction includes an explanation of doubled-up in their list that defines who is homeless, but if someone is not familiar with specific terminology or the law, it can be hard to figure out if they could be eligible for McKinney-Vento services. Building Changes’ reports on students homelessness in Washington’s public schools repeatedly show that a significant percentage of the homeless student population—74% during the 2018-2019 academic year—are living in doubled-up situations, contrary to the common belief that someone experiencing homelessness is unsheltered or living in a shelter, hotel, or motel.

For Amy, who is the director of state and federal programs at Longview Public Schools, what she sees in her community is similar to reported statewide data on students’ housing status. She said, “The vast majority of students experiencing homelessness in our school districts are doubled-up, which is a really important reason to get the word out because a lot of people that are doubled-up don’t see themselves as homeless.” In Longview’s public schools, 67% of students who are experiencing homelessness are living doubled-up. She also recognizes that families in her community may live together for economic and for cultural reasons and has found it helpful to have conversations with families to identify McKinney-Vento eligible students more accurately. The top three non-English languages spoken in Longview are Spanish, Vietnamese, and Chuukese. “Vietnamese-speaking students and Chuukese students are the ones that we’re noticing, especially during COVID-19, that they are not engaging as high as their non-Chuukese peers, and we’re working on ways to do better outreach,” Amy said.

Outreach efforts are even more important in the face of a pandemic

When three people from different parts of the educational system are having similar internal conversations about the need to improve outreach for students experiencing homelessness, asking each other “What if?” sparks ideas of what is possible. The story of how the updated flyer was created may have started with “What if?” but it was realized through a series of yeses.

“I was looking for a partner who would pick up and run with this and I sent it around to a lot of different folks. Building Changes jumped on board and said yes,” said Rose. Building Changes’ strength as an advocacy organization and as an intermediary between government agencies, schools, and community-based organizations helped connect Rose from OEO to Mehret at Building Changes.

When COVID-19 forced school buildings to close last year, Building Changes, with public and private partners, helped to distribute emergency funds to 199 organizations, schools, school districts, and tribes through the Washington State Student and Youth Homelessness and COVID-19 Response Fund. Mehret wanted to learn what communities’ highest needs were during the pandemic and was particularly interested in counties outside of King, Pierce, and Snohomish. She reached out to COVID-19 Response Fund recipients, and Amy from the Longview school district responded to her email.

“As a school district, and I don’t think we’re unique in this way, we relied quite heavily on the students being in school and staff. We were very dependent upon our teachers, our paraeducators, our administrators, our school nurses, our counselors, and even our school secretaries to help us identify and reach out to parents and children experiencing homelessness,” she said. “Without being in school much in the last year, we have found that our primary way of reaching students is not working for us; and therefore, it made this project even more important.”

In addition to school districts depending on staff to identify and support students, many without sufficient funding rely on staff to fill multiple roles. For example, school districts are required to provide McKinney-Vento liaisons to support students experiencing homelessness, but these liaisons often also support students in foster care. This can leave them with less capacity to fully support all students.

According to a 2019 report by the Office of the Washington State Auditor, school districts statewide dedicated an average of about 20 minutes to each student experiencing homelessness per month. “We know that districts are committed to supporting students, but their ability to get information out and to fully inform families to connect all potentially eligible students is limited,” Rose said. “My belief is that when communities hold knowledge about students’ rights, they’re better able to connect with those who need it,” she explained.

The importance of community engagement and representation

To ensure that the updated flyer was inclusive and accessible, the design team enlisted the help of the Longview school district community. Amy helped to create a focus group composed of McKinney-Vento liaisons, social workers, parents who were currently in doubled-up living situations, people who represented different cultural groups within Longview, and people who spoke the languages that the Longview and Kelso school districts were trying to reach. Some people in the community were familiar with the McKinney-Vento law, while some were not. Amy fielded additional feedback and shared it with Rose and Mehret. Rose facilitated the two-and-a-half-hour focus group meeting, while Mehret oversaw and organized the entire process.

The focus group meeting was an intentional, collaborative process. Participants were asked about which images, words, and messages worked; which aspects needed improvement; and if they felt that the updated flyer represented them as individuals and their community. “It was a process that involved community members and the people who participated in the focus group identified as being community connectors—people who might be the ones who share knowledge, ideally about the flyer,” Rose recalled.

Simultaneously, Mehret wanted to find a local artist who understood the power of representation and could bring Amy and Rose’s idea to life. She brought on board Gabriel Campanario, a Seattle-based illustrator, to create the updated McKinney-Vento flyer. “Showing diversity, not only in this flyer, but in all types of illustrations where people are represented, is essential. I wouldn’t be doing a good job as an illustrator if my artwork didn’t reflect the diverse communities it is meant to reach,” Gabriel said.

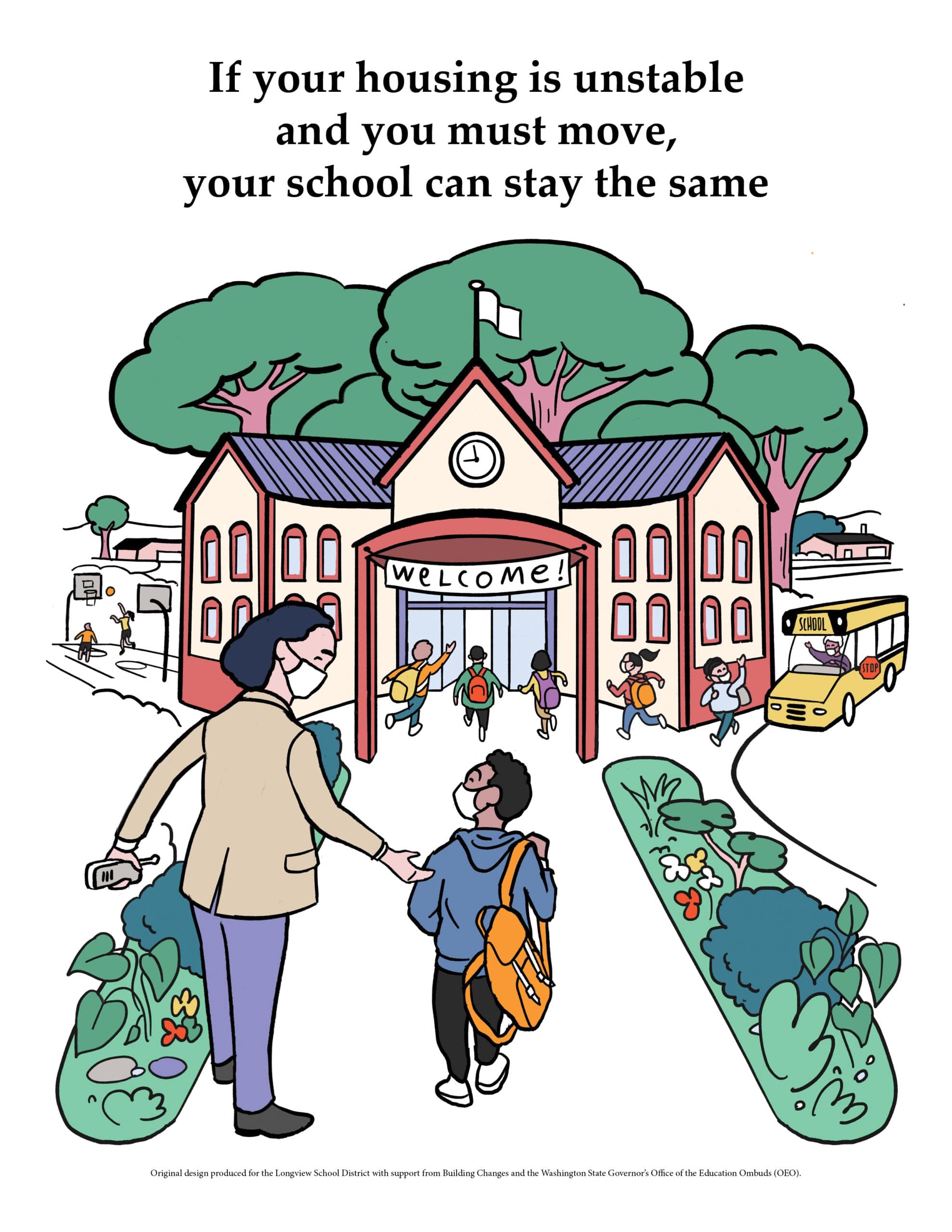

The final updated flyer is graphics-focused with drawings that show diverse families in different housing settings. Simplified text is matched with images that depict various services provided under the McKinney-Vento Act. Most importantly, it is much more straightforward and has one call to action: contact your local McKinney-Vento liaison for help if your housing situation is unstable.

“Just stay while we figure the rest of this out.”

For Rose, she believes that knowledge about McKinney-Vento services needs to be extended outside of schools to ensure more potential students are being identified early on and provided with the support they need on time. She said, “Sometimes, learning later down the line that a student might be eligible for McKinney-Vento has meant that you couldn’t put in place one of the key protections, which is to just stay in school, keep stable while we figure the rest of this out.”

Schools have long played the role of being a central resource and knowledge hub for communities. To ensure students and families experiencing homelessness are not left out in the educational system, outreach efforts inside and outside of schools must also be updated with the help of the communities themselves.